Coarsening Effects

Arguments have been made by artists that violence is a viable tool to produce art and have audiences interact with it in “authenticity”. The artists who make this claim cite artistic licence.They feel that they are not responsible for the effects their art will produce because “that is the art”. My own experience with such productions was with Isaac Nabwana’s production team as they filmed scenes at a music festival that included very disturbing gore. They put out a video (1) that if you observe, you’ll see audiences around them shocked and terrified. But these aren’t actors or extras, these were the festival attendants. Isaac saw it fit to create an environment of terror for cinematic effect.

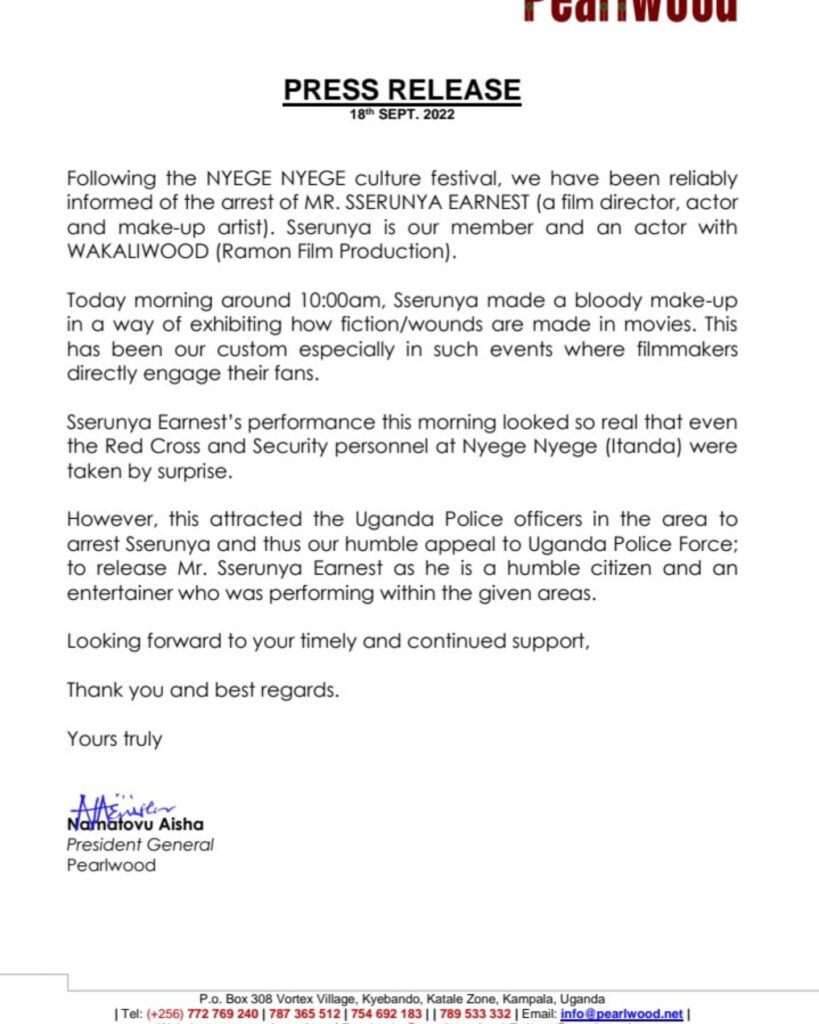

The assumption was that the audience would be so surprised by the ingenuity of the special effects and that we’d laud them for their immaculate acting. And even after the main actor of this film is arrested, the press release wakaliwood puts out is in demand for his release on the grounds that he is artistry. Even if they themselves admit that the special effects were so realistic it fooled security on the festival and a red cross team that was on site to treat any injured festival goers.

When I first talked of this incident at the festival, there were mainly three reactions; the first that I was not directly affected and I was trying to make a buck from the festival by suing and getting damages. And after I could be identified from the video the festival put out now, the second was that it was art and I had no right to get as offended as I did. The third is that I had access to the Nyege Nyege founders due to my proximity in the arts and that my response was unwarranted. However, since this happened up to today any communications that I have sent the festival and the Isaac Nabwana have not been responded to

In all the subsequent communications after the festival, this incident is not addressed, even by journalists covering the event. A New York Times article by Tom Faber waxes lyrical about how the festival is supporting artists and how the festival founders Dilsizian and Debru are innovating within the music industry. In one paragraph he hints about the festival failures to keep their audiences safe:

“Dilsizian and Debru chose to embrace the chaos, trusting in their D.I.Y. ethos and last-minute problem solving. But at the festival this year, that meant campsites and facilities were half-finished, and several attendees said that problems with security at the event seemed more severe than at other editions, with reports ranging from pickpocketing to more serious assaults, despite a large police and armed military presence.

Nevertheless, the majority of festival goers just seemed intent on enjoying the impressive diversity of music on offer.”

There was no journalistic inquiry on the side of the Times. The structural issues that cause issues like what happened with Wakaliwood were simply overlooked, for example this paragraph:

“As two white European men helming an organization that largely promotes Black African artists, Dilsizian and Debru said they think critically about Nyege Nyege’s hierarchy, and are wary of adding to the continent’s colonial history of exploitation.

“Would it have been better if this was run by people from Uganda? Obviously” Dilsizian said. “But it didn’t happen, I guess for so many reasons.”

This journalist doesn’t even bother to ask for even one of the very many reasons. And this not to say I’m interested in knowing why, I aim to show you how this lack of cultural direction causes harm that these people and people with proximity to whiteness will most likely never be held accountable for.

Isaac Nabwana got his big break when one of his film’s “who killed captain Alex” went viral on the internet. The movie is a low-budget action thriller about political assassinations and the likes, through the attention they garnered, they attracted mostly white collaborators that have helped them gain entry to some of the most prestigious cultural exchange programs today one of their latest highlights being documenta fifteen. To build careers and to achieve success most of these artists use all the means at their disposal to reach the West. After all that’s where most cultural financing comes from, governments locally have little to no provisions for this so it’s understandable.

The director Isaac Nabwana has built a career of fetishizing violence on Black bodies and for anyone who thinks this critique is harsh or severe, ask yourself why he is comfortable employing an actor and shooting that scene. He expects that such a display of grotesque violence will not be of shock and that if it is black bodies they are so accustomed to violence that’s it’s meticulous recreation should be cause for applause, and that even when an arrest is made because of this performance for the people of Ramon Film Studios it is unexpected. There can be no logical reason from their perspective on why this could have happened.

I’m not saying that the intention of Wakaliwood is malice. This is just a case of negligence that was avoidable. This company through creative means has grown a huge international audience for their work, but this work is done amongst people who have lived the realities their movies parody. My critic is the tools Ramon is using now and the platforms enabling this form of filmmaking. The main actor in a news source after his release says “The truth is, If I had informed the police earlier before acting, I wouldn’t have got what I wanted because they would be aware of what I was going to do.”

Ramon and Nyege Nyege are a perfect example of what is happening now in most Ugandan cultural productions, and this is that there is little to no accountability for the audiences cultural funds aim to support since there is little to no oversight from where the money is coming from. Most cultural producers here don’t follow any ethical considerations and are most times not even expected to (the reasons for this require another publication entirely). If you think this assumption is far-fetched, let’s consider this:

Section 1 of the Basic Law (Grundgesetz) in Germany, has a clause that stipulates that media presentations have a coarsening effect if “scenes of death and carnage are depicted in detail as ends in themselves.” Uganda also has its stage plays and entertainment act, although the considerations for censorship are not clearly defined (this is also subject to another article), however even as vague as it is, it makes considerations for any public performances that “breach the peace” to be censored. But It is not only censorship and didacticism that motivate regulation, the misuse of artistic license is not far fetched, and to observe this I ask these questions; Why didn’t they hire extras? Why don’t I have a choice on whether or not to participate in this production? Why didn’t they communicate this as part of the experience? Why is the festival okay with this approach?

The Kulturstiftung Des Bundes basically aided an organization and event that disregarded German regulation. The festival organizers probably know this and have refused to offer accountability to the people affected by their negligence, this is because the festival founders and Ramon Film Productions have no incentive to engage local audiences. Even when the Nyege Nyege team promised an entire parliament because there was massive suspicion on the side of legislators that their festival would be safe, they have offered no accountability for acts of violence and insecurity at this festival. There may be no repercussions for Nyege Nyege as a festival and for Ramon Film Studios because they have no local source for their funding. That even when the commercial aspects of this festival through negligence break duties of care for people who purchased tickets the legal system is so bad that aggrieved people will find no redress, the festival counts on this to avoid being held accountable.

There are two ways to remedy this, and the first is that the onus is on local cultural producers, that as you get support from funding organizations to study the ethical considerations of your work, and for funding organizations to scrutinize programming and collaborations of the programs being funded. Because if neither do so the extremely problematic nature of what happened at Nyege Nyege will continue to go unabated.