La Biennale di Venezia mi rende cinico.

Introduction.

The premise of this article is based on my personal interactions with all the parties involved in the inauguration of the Ugandan Venice Pavilion. Throughout this process, I engaged with Pamela Acaye, Collin Sekajugo, and Bjorn Stern, who served as the project’s patron. When concerns arose, including my own, regarding certain aspects of the project, Acaye dismissed them by emphasizing that the primary goal was to foster exchange and encourage a broader perspective. She believed that the project should be viewed through this lens. It seemed irrelevant to her that the collaboration involved a nation-state with a history of violence, through the Ministry of Gender, Labor, and Social Development, or that the patron had hired a curator with no direct connection to the cultural context of Uganda.

Upon requesting an interview with Stern and expressing my concerns, his initial response contained a thought-provoking statement: “Abstraction is not a refuge into dreams nor disassociation. It speaks directly to phenomenology and the senses, which is something that is present and palpable in Uganda, underneath the everyday quarrels of semantics and carriers of self-interest.”

This statement seems to imply that Ugandan art is not as sophisticated as Western art, and that it is only valuable for its sensory qualities and it also appeared that the profit gained from the sale of these works by all parties involved was inconsequential. When questioned about agency, Stern pointed out that the global art market’s value is almost twice that of Uganda’s entire national economy. I was essentially told that I should be grateful for the opportunity to be in Europe and that the means employed should not be scrutinized. According to their perspective, since we had achieved the desired outcome, we could determine the future direction from this point. However, with the preparations for the 2024 edition underway, I cannot help but wonder if this narrative is deceiving.

As the next edition of the biennial approaches, the dominant presence remains unchanged: whiteness. What happens to the questions that you claimed to be pleasantly surprised to hear a year later when you have failed to provide clear answers, even when given the opportunity? I am publishing this article to ensure that art history accurately reflects the underlying power dynamics within this exchange. I am doing so not only because of my personal interest in the field of public art but also because it would be disingenuous to myself if I did not.

Trevor Mukholi.

The article;

at the Venice Biennale the international community convenes to witness the best in global cultural production, global discourses are built here, experiences are shared through aesthetic and intellectual interventions, the format of the Biennale is ingenious, it provides a potent platform for different cultural producers to transmit human experience and cultural innovation, however because it does this so well it becomes strategic for both capital and empire, for empire the Biennale is an arena for legitimacy and for capital the Biennale becomes a mechanism for creating and establishing value. the role of the art market in the Venice Biennale is entrenched right at inception; this is not to imply that having a market in places of cultural exchange is inherently injurious, I want to show how this relationship that was fostered early from this event has evolved to stifle meaningful cultural exchange, which then stunts cultural production in spaces that are now only beginning to culturally recover.

The narrative above is not new, this conversation was started long ago, and the Biennale solved for this by banning the sale of the artworks in the exhibition, and technically one cannot purchase artworks in this exhibition, but galleries circumvent this by becoming patrons to the artists participating for their national pavilion. When asked whether this brings about whether this affects the quality of exhibition, gallerists typically respond like this.

“according to Paola Potena, director at Milan’s Galleria Lia Rumma—whose installation artist Gian Maria Tosatti is representing Italy at the Biennale this year—the curatorial rigor of the Venice Biennale is what sets it apart from other art events. “This [neutrality] generates a special attention…towards all the artistic projects presented and therefore also an increase from a commercial point of view,” she said. Potena noted that part of the gallery’s support of Tosatti had come in the form of fundraising for the work he will present at the Italian pavilion through a network of collectors and sponsors. For Potena, this is a natural part of how the Biennale comes to fruition: “As long as the curatorial choices of public events are independent, I don’t see any friction if private supporters intervene to help projects. They all work toward the same goal: that of promoting art and artists.” *

The argument is that the curatorial independence of the Biennale sets it apart from other systems of cultural exchange that have either fallen prey to or are as a result of the need for capital to expand, the authenticity of representation is absolute through this curatorial autonomy, and for countries that have can afford that autonomy, independent aesthetic interventions can be realized. however for countries that cannot, their agency is used as an instrument to culturally legitimize and create economic value for aesthetic objects, and this is not the first time this is happening at the Venice Biennale, pavilions from African countries have been hijacked by dealers to stage exhibitions for artists they represent, while the ethical considerations of this may be up to debate, the real danger with this is how curatorial agency is retooled to withdraw/inhibit agency and circulate it to maintain longstanding stilted cultural power dynamics.

Shaheen Merali (born 1959) the curator for the inaugural Ugandan pavilion at Venice is a Tanzanian writer, curator, critic, and artist. Merali began his artistic practice in the 1980s committing to social, political and personal narratives. As his practice evolved, he focused on functions of a curator, lecturer and critic and has now moved into the sphere of writing. Previously he was a key lecturer at Central Saint Martins School of Art (1995-2003), a visiting lecturer and researcher at the University of Westminster (1997-2003) and the Head of the Department of Exhibition, Film and New Media at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin (2003-2008).A regular speaker on ideas of contemporary exhibition making internationally, in 2018 he was the keynote speaker at the International Art Gallery of the Aga Khan Diamond Jubilee Arts Festival, Lisbon.

He exists only to legitimize this project, and if this seems reactionary and “nationalist” I ask if Uganda has a “a fast-paced economy from which a cultural environment has taken root, one that that embraces contemporary Africanity” then was there no one skilled individual capable enough to engage with existing cultural production here? “Contemporary Africanacity” is simply a vehicle for cultural extractivism, this is not a critique of commercial art institutions it is one of commercial institutions that manipulate complex cultural ecosystems for the profit of themselves and chosen collaborators, this is not the first time this is happening at Venice, in this very Biennale Namibian cultural producers signed a petition to have their pavilion withdrawn, because of the very same issue facing the Uganda pavilion , curatorial practice had been used to take away agency from cultural producers and redirected to profiteering, the biggest issue this presents is a deep cynicism in the art scenes where this happens, artists realize that working from the local will not advance their careers and for them to get global audiences and platforms they will have to pander to the tastes of (mostly white) dealers, collectors and gallerists; in a commercial settings, free markets will lean towards this as the aforementioned audience has the resources to be patrons and to purchase artwork, but when their influence extends directly into the cultural production that represents communities, agency is stifled and artist practices in these communities are severely affected, since they are working outside their communities they feel that any critique about their work even when it is at a platform for representation is unwarranted or not good enough.

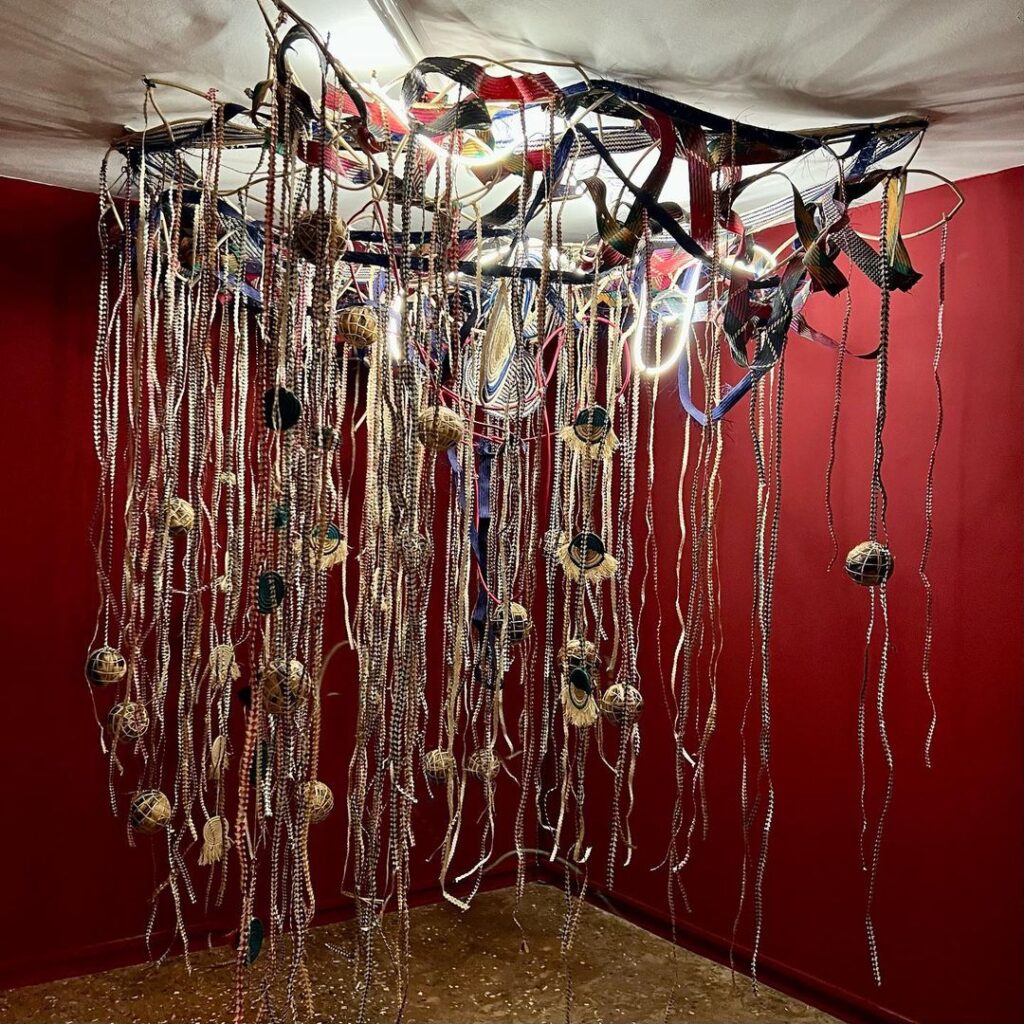

This brings us to Pamela Acaye, she is an artist who uses multiple media, music, performance, and visual arts, she has worked in multiple spaces to realize performances, installations as well as exhibitions, I commented about her work in the Venice Biennale not being conceptually strong to which she replied that I’m not intellectually equipped to make this argument, I went further and tried to engage Merali on the same concerns by asking him questions pertaining to this exhibition after he shared that he was discussing concerns pertaining to epistemic justice still at Venice I did this because of how the curatorial approach is laid out, this is an expository exhibition for the country and whilst one might argue it’d be better to select artists that actively shifted culture so as for us to arrive at the contemporary.

“Uganda, especially its capital city Kampala and its second city Jinja, has provided a fast-paced economy from which a cultural environment has taken root, one that that embraces contemporary Africanity in terms of its relationship to design, text, exhibition-making, performance, and context.”

The description of the pavilion doesn’t give any nuance in how they describe cultural production here, the “cultural environment” has not taken root, there are no functioning state public art initiatives, there are no contemporary art museums, local contemporary practice is just now being accepted in academia, and while cultural institutions are making large strides in supporting cultural production, critical cultural discourse has been erased by this description, it enables the curator to merely select as they please this is because they place artists in positions of reference mostly to the west,

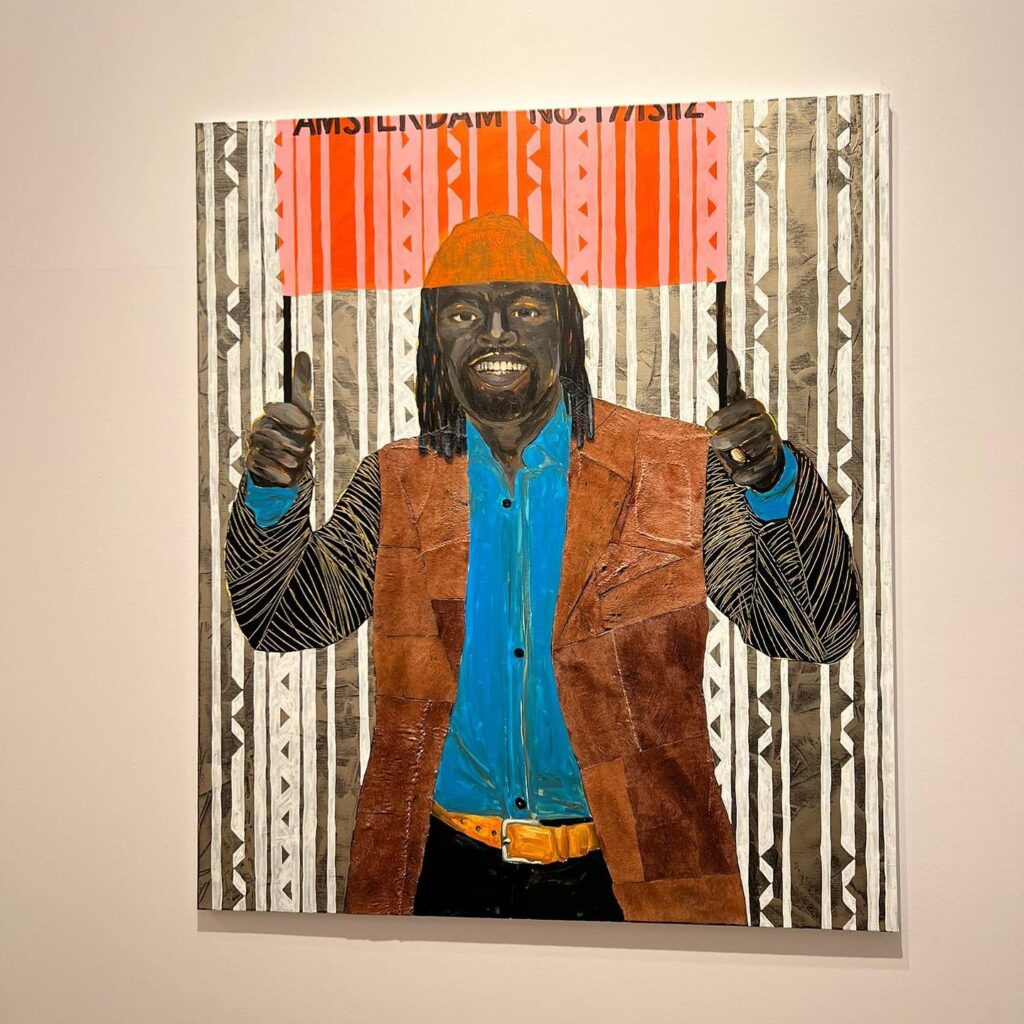

“Sekajugo has worked with the manipulation of the common stock image to reveal its inherent biases of entitlement and privilege largely modelled on the Western self. Sekajugo’s artistic practice highlights a contemporaneous anthropological reversal of this mainstream culture through the lens of a decidedly African sense for irreverence and play on the ad-hoc. Conceptually,”

This statement under Sekajugo’s profile describing his practice puts all his artistic acts only in reference to the west, he intently seeks this image out, then models this image to reflect the image he drew it out of and finally finds resources to show this image back to the body that it was made from, this obsession with the reproduction of self is problematic when discussing a body work that aims to achieve cultural exchange and representation, and this observation is not because the work fails but because it succeeds, how does the stock image have “inherent biases of entitlement and privilege largely modelled on the Western self” the stock image is created to be blank it is as a result of a particular culture trying to represent itself in image even when that image isn’t tied to a wider coherent body of work, but why does Sekajugo burden himself to represent the western self at the inaugural pavilion at the Venice Biennale, and why is it an “anthropological reversal” when Sekajugo studies and models these systems. is there an anthropological movement that Sekajugo must reverse through? And is this dichotomy necessary?

“The act of re-installing these deconstructed materials is a response to the agency of women’s work in Africa and an acknowledgment of the role that this artistic labor plays in the climate ecosystem.”

How are the materials deconstructed and what is the significance of this deconstruction, how is it necessary? how does the curator disseminate this information? because at such stages curating is pedagogy and if the end goal is intellectual gymnastics, then how does that contribute to a discourse if meaning is obscured? And the criticism I levy against Merali for his choice of artists is not on his failure to articulate their practices, its on how he approaches what he considers the Ugandan modern, why does he place these artists outside an aesthetic narrative? For someone trying to get an “audience to further understand the semantic intelligence of African and in this case Ugandan traditions and its modernity.” he chooses to begin from the very end of this progression and does not give any internal (Ugandan) reference points from where this aestheticizing begins he only links this work in the case of Acaye’s work to activism which brings us to another point of critique, Merali intends to show that Acaye transforms “utilitarian” material and “artisan crafts” to make it tell new stories but doesn’t this bring it back to a utility and then if it does why is Acaye’s application different? And where is the new story it is telling and why is Venice the best place to tell it? These questions are rhetorical, if Merali was interested in telling the evolution of Uganda’s modern aestheticizing, he could have studied artists that successfully innovated using images still rooted in traditional “Uganda” and made them modern, artists like Theresa Musoke or if he wanted a current artist practice that can be traced back to a “Ugandan” traditional (and I quote the term Ugandan because it is problematic when discussing cultural histories here) he could have examined Xenson Senkaaba’s practice.

The Uganda pavilion at the Venice biennale is not representative of cultural production in the country, what happened here is when curating becomes an end in its own, it becomes a tool of cultural recuperation in contexts that are already suffering cultural erasure because of this.

I think this quote from Freire speaks to this situation and that’s why I’m including it, as an epilogue.

“Theirs is a fundamental role, and has been so throughout the history of this struggle. It happens, however, that as they cease to be exploiters or indifferent spectators or simply the heirs of exploitation and move to the side of the exploited, they almost always bring with them the marks of their origin: their prejudices and their deformations, which include a lack of confidence in the people’s ability to think, to want, and to know. Accordingly, these adherents to the people’s cause constantly run the risk of falling into a type of generosity as malefic as that of the oppressors.”

Curating is supposed to aid meaningful cultural exchange which can only happen if agency is returned to local institutions, it’ll reflect in the diversity of the exchange but it will also communicate authentic cultural experience which is the cardinal aim of an exhibition at the scale of the Venice Biennale.